History of the New York City Emergency Medical Service-

Draft/ still in progress-

by Mark Peck

In the early 19th century, New Yorkers suffering major medical events or significant trauma had to utilize any means available to reach medical care. They were carried, dragged, placed upon hand carts, or any available wagon, and taken to their homes to await the summoned physician, or to one of the many clinics and hospitals opening in the rapidly growing city. There was little concern for control of bleeding, or immobilization of broken limbs. It was frequently a time consuming and painful journey that worsened the patients’ condition, or contributed to their demise.

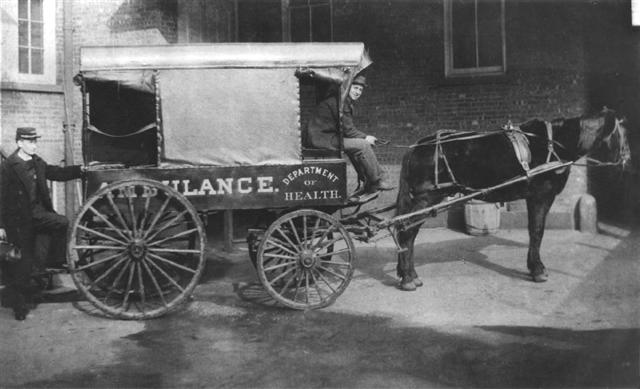

Following the Civil War, a returning U.S. Army surgeon, Dr. Edward B. Dalton, brought his experience with the military ambulance service to the attention of the New York Hospital Board. He persuaded them to create the nation’s first hospital based municipal ambulance service at Bellevue Hospital. The first of five horse drawn ambulances initiated service in June 1869, staffed with a hospital intern and a teamster.

The commissioners authorized two ambulances for Bellevue Hospital of the type recommended by Dr. Dalton. Furthermore, “Each ambulance shall have a box beneath the driver’s seat, containing a quart flask of brandy, two tourniquets, a half-dozen bandages, a half-dozen small sponges, some splint material, pieces of old blankets for padding, strips of various lengths with buckles, and a two-ounce vial of persulphate of iron.” The Abbott-Downing Company was chosen to construct the vehicles, and in June 1869, the world’s first hospital ambulance service trotted into action at New York’s Bellevue Hospital.

The venture into emergency medical services proved such a success that five more ambulances and horses were added the following year. By 1891 Bellevue had 4,392 ambulance calls, but by that time a service at Chambers Street had 3,021 calls and ambulance service was also available at New York, Roosevelt, St. Vincent’s and Presbyterian Hospitals. Ambulance drivers had to be familiar with the geography and traffic flow of the city. An ambulance was given the right of way over all other vehicles except fire department apparatus and US mail wagons.

Ambulances were of high quality construction and weighed only 600 to 800 pounds. A movable floor could be drawn out to receive the patient, designed for easy cleaning and disinfection. A drop or “snap” harness was used and the corps took pride in rapid response to emergencies. It was claimed that an ambulance could travel a mile in five to eight minutes in the business district. The ambulance carried a stretcher, splints, cotton and oakum. Equipment also included handcuffs and a straitjacket. The surgeon’s bag included medications, antiseptics and gauze.

It is a testimonial to the soundness of Dr. Dalton’s concept and the brilliance of his organizational ability that the ambulance service continued into the era of motorization. In medical emergencies, where prompt intervention is essential, the ambulance has proved its value on countless occasions.

The success of New York City’s ambulance was soon noticed across the East River in the City of Brooklyn, where the first call to for it’s own organized ambulance service came in 1871. For another two years, the headlines and editorials of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle cited case after case of unnecessary death and suffering. One editorial even noted that the horses of the city fared better than its citizens “Let a sick or maimed horse be found on the street and Bergh’s men would be on hand immediately with an expressly built apparatus upon which the horse would be placed with gentleness and care, carried to the stables in Williamsburg.”

In 1873 the City of Brooklyn initiated ambulance service at Long Island College Hospital and Eastern District Hospital, dispatched via telegraph connected to the Police and Fire Departments. The ambulances were owned by the Department of Health and staffed by surgeons from the hospitals, while private stables provided the horses and teamsters. The LICH stable was on the north side of Pacific Street, across from the hospital. In the years that followed the City funded additional ambulances stationed at both municipal and private hospitals. Telephones replaced the telegraph system as this new form of communication expanded.

In 1873 the City of Brooklyn initiated ambulance service at Long Island College Hospital and Eastern District Hospital, dispatched via telegraph connected to the Police and Fire Departments. The ambulances were owned by the Department of Health and staffed by surgeons from the hospitals, while private stables provided the horses and teamsters. The LICH stable was on the north side of Pacific Street, across from the hospital. In the years that followed the City funded additional ambulances stationed at both municipal and private hospitals. Telephones replaced the telegraph system as this new form of communication expanded.

1898 brought the consolidation of Brooklyn, Queens, The Bronx and Staten Island into the City of New York, with many public services merging into unified departments. Municipal ambulance services continued to be provided by the Department of Health, as well as the Department of Public Charities, which operated the City hospitals in Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island.

As it was usually a police officer that placed the call for an ambulance, the Police Commissioner, while having no statutory right or responsibility, became the defacto regulator of ambulances, designating each hospital’s response area. Requests were routed by the officer through his precinct, forwarded to police headquarters, and then to the hospital. Some hospitals even refused to assign an ambulance until a police officer arrived at the scene and confirmed its need.

The assignment of a response district to a hospital was not always done with ambulance response time in mind. Often the hospital was situated at an outer edge of the boundary, and on occasion the hospital was actually outside its assigned district.

From 1909 until 1929 all ambulances officially came under the jurisdiction of the Board of Ambulance Service, headed by the Police Commissioner. This period saw motorized ambulances starting to replace horse drawn ambulances although many hospitals still found these new automobiles not nearly as reliable or swift.

By 1923 all the horses had departed from Bellevue Hospital’s stables. Ambulances from 12 municipal and 33 private hospitals were answering the 343,000 annual emergency calls of New Yorkers. An intern and a driver still staffed ambulances, but the intern often had responsibilities within the hospital, and was called out only when needed for ambulance duty. As the call volume rose, if a doctor was not available, an orderly or even a janitor could be enlisted to man the ambulance.

World War II brought a pressing need for physicians in the military, and in February 1942 the Department of Hospitals replaced all interns on ambulances with attendants. All but 5 of the voluntary hospitals did likewise. Most major cities in the U.S. had already ended the staffing of ambulances with physicians. Physicians now were dispatched only on certain calls considered true medical emergencies by the Police Department, such as heart conditions, maternity cases, drownings, suspected deaths, and serious accidents. The determination to assign a physician was largely based on the requesting Police Officers personal experience and judgment rather than established criteria.

Following the war, the staffing requirements for ambulances were again debated. Many interns felt that their skills and training were wasted on ambulance assignments due to the high percentage of minor and unnecessary calls. Some were concerned about the risk of ambulance accidents and of being robbed of the narcotics that they carried. The hospitals on the other hand, believed that having interns perform ambulance rotations increased their awareness of the social needs and living conditions of their patients. There was also a large financial incentive for the hospitals, as interns’ salary was considerably less than the lesser trained attendant.

The decision of staffing levels was left to the individual hospitals, which now only had to satisfy the minimum requirement that the attendant be “competent”, and possess a Red Cross First Aid Certificate.

By November 1948, public pressure forced the municipal hospitals to again assign interns to the majority of the ambulance calls, despite the findings of a study of 46 major cities conducted by the American Municipal Association. The study concluded that” A physicians’ presence on all ambulance calls, as a routine matter, is definitely not indicated. A trained attendant does just as well or better, because he is specifically trained for the job”.

Little changed until 1962, when many interns became concerned about the cost of liability insurance for their activities outside the hospital. Call volume had reached 400,000 requests a year. The Department of Hospitals replaced the interns with Ambulance Attendants selected from the ranks of the hospital ward attendants. Often they had minimal formal training, and learned “on the job” from their peers. Union representation for Ambulance Attendants was provided by the Hospital Technician’s Local 420, and for Motor Vehicle Operators by Local 983, of District Council 37.

Training improved in 1967 as Ambulance Attendants were upgraded to Ambulance Technicians. The “trail and error” method of training was over, with a formal training course taught at New York City Community College. However the Motor Vehicle Operator still had no patient care training or responsibility.

In 1969 the Department of Hospitals organized all ambulances from the 17 city owned hospitals into a centralized Ambulance and Transportation Service.

Sweeping changes in EMS started in the 70’s

In 1970 the state legislature replaced the Department of Hospitals with a public service corporation. Responsibility for coordination of the ambulance services in New York City was transferred to the Division of Emergency Medical Services of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation.

The Federal EMS Systems Act of 1973 influenced vast changes in the provision of prehospital care nationwide, with seed funding provided to improve training, coordination, staffing, administration, communications and equipment. New York City EMS took full advantage of this money by requiring all its personnel to upgrade to the level of Emergency Medical Technician. The MVO and Ambulance Technicians were cross trained in vehicle operation and patient care, and their duties combined into the title of Ambulance Corpsman. Motor Vehicle Foremen and Senior Ambulance Technician’s became Supervising Ambulance Corpsmen. The unique responsibilities of these new titles emphasized the need for separate union representation, and Local 2507 was created. It soon became apparent that there were conflicting interests having supervisors within the same local as those they supervise, and the Supervising Ambulance Corpsmen soon split into their own Local 3621.

The EMS Systems Act also prompted development of designated specialty care centers for the treatment of Burns, Trauma, Microsurgical Replantation, Hyperbaric Oxygen, and Venomous Snake Bites.

Paramedic Ambulances in the Bronx

Funding was also provided for a pilot Paramedic program. Spurred by the success of programs in Los Angeles and Seattle, and highlighted every Saturday night on the TV show EMERGENCY !, New Yorkers soon learned that many life saving procedures which were previously limited to the hospital setting, could be brought into their homes, increasing their survival of heart attacks and other major illnesses. The first group of 21 Ambulance Technicians, MVO’s and Supervisors commenced their EMT and Paramedic training in 1974 at the Institute of Emergency Medicine of the Albert Einstein School of Medicine. Dr. Sheldon Jacobson, Director of the Emergency Department at Jacobi Hospital, served as Medical Director for all paramedic training at IEM.

Paramedic training focused on many of the advanced skills taught to physicians who specialize in emergency medicine. Starting with a background program of anatomy, physiology, cardiac electrophysiology and pharmacology, the program then taught the paramedic students to interpret electrocardiograms, perform detailed physical examinations, interpret blood gases, initiate intravenous infusions, calculate medication dosages and administer appropriate medications. The paramedics were also trained to perform endotracheal intubation (inserting a tube into the trachea in order to facilitate ventilation and prevent aspiration of vomitus), a procedure previously restricted primarily to anesthesiologists.

The paramedic students then were assigned to months of clinical rotations in the Adult Emergency Department, Pediatric Emergency Department, the Psychiatric Emergency Department, the Operating Room, and Obstetrics, where they perfected the skills learned under physician supervision. The total training time exceeded 1200 hours.

More importantly, paramedic training stressed the skills needed for the paramedic to independently correlate all the information collected from a patient, determine a provisional diagnosis, choose one or more predefined treatment protocols and initiate them in order of priority. Unlike the program in Los Angeles which required that the paramedic make radio contact with a physician before beginning any advanced care, New York City Paramedics initiate most treatment from predefined standing orders, markedly reducing the time needed to treat a critical patient. Radio or telephone contact with a physician is only required after preliminary treatment is completed, or when the paramedic desires to consult the physician for advice on unusually complicated cases. The Jacobi 1 class graduated on August 21, 1974.

Medic One and Medic Two went into service at Bronx Municipal Hospital (Jacobi Hospital) on July 7,1974, capable for the first time of recording and interpreting EKG’s, defibrillation and cardioversion, intravenous therapy, and administration of medications to control cardiac arrhythmias, support blood pressure, correct diabetic emergencies, allergic reactions, narcotic overdoses, seizures and severe respiratory problems. Early equipment was heavy and cumbersome compared to that used today. The Physio-Control LifePak 4 weighed 45 lbs compared to a Lifepak 12 which weighs 18 lbs. Medics also carried a large 747 fishing tackle box for drugs, and a dual tank Robertshaw demand valve/resuscitator. They also pioneered the use of nitrous oxide in the field as a non-narcotic analgesic.

Class Roster Dr. Sheldon Jacobson, Medical Director

Ricky Attanasio | Mike Garufi | Richard McAllan | Charles Williams |

Kevin Brown | Mark Herzenberg | Winston Moorehead | |

Anthony Ciorciari | Richard Kunze | Phil Nelson | |

McNeil Cross | Gary Lombardi | Paul Rifkin | |

Tom Dean | Ron Maffei | Mark Rothstein | |

Rodney Dreyfuss | Jose Martinez | Anthony Shallash | |

Ambulance Deployment

Strategic location of ambulances was never really a consideration for the first century of ambulance service in New York City. Ambulances were dispatched from a stable or garage near the hospital where its medical staff worked when not on an assignment. Even through the 60’s and 70’s, all available ambulances assigned to that facility remained in one central station until needed for an assignment, much as the fire department does with its apparatus. When an assignment was transmitted to the station, the “Next Up” crew would be handed the call. Certain stations experimented with a system of assigning one particular unit to handle all calls received within a specific precinct, but this soon proved unreasonable, as certain precincts were busier than others, placing a heavy workload on some units, and minimal work on others.

In 1976 NYC*EMS attempted a radical departure from this time honored method. Roving Deployment was based upon the police department model, in which vehicles awaiting an assignment patrol a designated precinct sector, placing them closer to a potential call and reducing response time. The program was highly successful in cutting response time and was expanded citywide. This later changed to assigning ambulances to remain closer to designated intersections throughout the city called Cross Street Locations.

Following the merger with FDNY, a Batallion Based Deployment method was tested in 1997, utilizing a system that the Fire Department continued to find successful for their fire companies. The department envisioned integrating all the ambulances and fire companies into a unified Fire Batallion, with ambulances housed at many new planned ambulance stations. Units throughout the city received new radio designations based upon the Fire Dept Battalion in which they were assigned, and several units were stationed at an intersection that might eventually host a new station. When an ambulance completed an assignment, it would theoretically return to its “Station” to await its next run, as a fire truck does.

This plan was unsuccessful for several reasons. First, call volume greatly exceeded the number of units available, resulting in units responding to one call after another, rarely returning to their stations. This deployment model had not considered that in ambulance assignments, there is a third leg of the journey that fire trucks do not travel- the transport to and from the hospital. This often places the ambulance great distances from its station for its next response within its home Battalion. If the dispatcher placed the unit unavailable until it returned to its station, it frequently caused that ambulance, which might be only blocks away from a critical patient, to be ignored while another ambulance assigned to cover calls within that battalion would be selected even though it was miles away at another hospital or prior assignment. Response times suffered, and the system was eventually returned to the previous CSL deployment. The department also encountered more difficulty than anticipated in acquiring land upon which to build these new stations, and as a result, the number of promised new stations was downsized several times.

NYC*EMS is Designated the Coordinating Agency for Emergency Medical Care

1977 brought two major changes in NYC*EMS. Executive Order 96 was issued by Mayor Abraham Beame, officially designating NYC*EMS as the coordinating agency for prehospital care within the city. EMS became officially responsible for disaster planning and coordination of resources not normally involved in the 911 system. While NYC*EMS had been performing many of these tasks for years, there now was a clear delineation of responsibility among the other public safety agencies.

During major disasters, a predetermined incident command structure now existed to coordinate EMS operations. This leadership role, which could not be accomplished within a system of unrelated independent ambulance services, greatly enhanced the ability of all ambulances in the system to work as a team. Additional ambulances run by the numerous volunteer and commercial ambulance companies, as well as EMS services from Long Island and New Jersey, could be accessed for Mutual Aid during times of crisis. A Mutual Aid Radio System was established to provide a common channel for communications with these agencies. This ability to coordinate these many services faced it toughest test during the World Trade Center bombing.

Training

The city also committed to an ongoing schedule of paramedic training. The second Jacobi Medic class graduated in December 1977, expanding the communities protected by paramedic ambulances. In addition to Bronx Municipal Hospital, Medic units were now based out of Bellevue Hospital, Kings County Hospital and Metropolitan Hospital. The Institute of Emergency Medicine continued to graduate 2 classes of paramedics per year for the next few years, with paramedic medic stations expanding to Seaview Hospital, Elmhurst Hospital, Lincoln Hospital, Queens General Hospital, Harlem Hospital, and Rockaway and Liberty Outposts.

Improvements in training continued to be a focus of the Emergency Medical Service, as they opened their own NYC*EMS Academy in 1978, in a wing of the Nurses Residence of Queens General Hospital. NYC*EMS now had adequate staff and space to conduct expanded training for new employees, refresher training for EMT’s (and eventually paramedics) and also provided one of New York State’s initial Certified First Responder classes for FDNY personnel.

From 1982 to 1985, the Bellevue Emergency Care Institute ran an additional paramedic training site in order to accelerate expansion of basic paramedic training. Eventually it replaced the IEM program.

In 1985 the EMS Academy (renamed the Division of Training) moved to its own building in Fort Totten and assumed responsibility for all EMT, Paramedic, Supervisor and Communications training. Paramedic Training and recertification shifted from the Bellevue Emergency Care Institute with the first DOT Paramedic class graduated in June 1986.

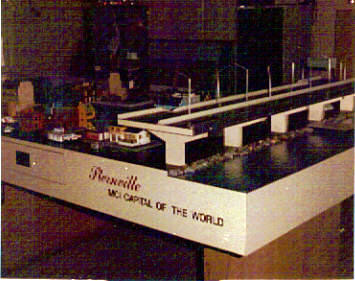

Sternville-a table top MCI training exercise for new supervisors

Sternville-a table top MCI training exercise for new supervisors

In 1992 the Division’s Instructors became responsible for upgrading all FDNY firefighters to Certified First Responder-Defibrillation. Following the merger with FDNY in 1996, the DOT was redesignated part of the FDNY Bureau of Training.

EMT-Defibrillation

Another major stride in increasing New Yorkers survival of sudden cardiac death came in 1989, when NYC*EMS equipped all of its Basic life Support Ambulances with Automated External Defibrillators. For years, the medical community had shown that the key to successful resuscitation in a sudden cardiac arrest is early CPR and defibrillation. It is one of the premises upon which the paramedic program was founded, but paramedic training involved long term, expensive training.

As computer technology continued to evolve, it became possible to program a computer chip to recognize and defibrillate the few cardiac rhythms that would safely respond to defibrillation. All of the services Corpsmen and Supervisors were trained in defibrillation, making the entire EMS fleet capable of that one survival critical step- defibrillation.

While Semiautomatic Defibrillation is now taught as part of every basic EMT course in New York State, the device is still not mandatory on every ambulance in the state. The majority of commercial and volunteer ambulances are still not equipped with defibrillators.

Asthma Initiatives

In February 1999 the New York City Health Department and the Health and Hospitals Corporation began programs to reduce the rapidly increasing number of hospitalizations and deaths from asthma in the city. FDNY*EMS joined them by participating in a state sanctioned pilot program to evaluate if EMT’s could safely diagnose and administer the nebulized bronchodilator Albuterol to patients suffering an acute asthma attack.

Albuterol is a relatively safe yet life saving medication that can reverse the oxygen blocking airway spasm and constriction of an asthma attack. It is delivered to the patient through an oxygen powered inhalation device. Previously, state law restricted medication administration to paramedics. To date, this program has been highly successful and is now a permanent part of the EMT training program.

COMMUNICATIONS

During the 50’s and 60’s ambulances were dispatched over the NYPD radio system from its borough communications centers. New York City became the first city in the nation to implement a 911 system in 1969, and all borough communications operations were moved to 240 Centre Street, with four consoles designated for ambulance dispatch and staffed by ambulance personnel familiar with the operation of the system.

The majority of EMS radio communications moved from the shared NYPD radio system to two new radio frequencies dedicated only to EMS calls, improving the speed of radio transmissions for both agencies. One VHF channel was assigned to Brooklyn and Queens units, and the other Manhattan and Bronx units. Staten Island was able to remain on the Staten Island NYPD channel due to the continuing low volume of assignments in the borough. A Registered Nurse call screening program was implemented to try to eliminate some of the non-emergent ambulance requests.

In May 1972 NYC*EMS operations moved to new headquarters at 377 Broadway in Manhattan. Administrative offices resided on the 10th floor, while a new Communications Center opened in the penthouse.

As a call came into 911, it was answered by a Police Communications Technician at 1 Police Plaza, who took the preliminary information and then connected the caller to the Ambulance Receiving Operator in the EMS Communications Bureau. Additional information was obtained from the caller to enable the ARO to assign a call type and priority, and first aid instructions were often given to the caller. The information was recorded on a card, which was then sent on a conveyor belt to the appropriate borough dispatcher. At the borough console the card was stamped in a time clock as the call progressed through each step of the system. The status of each ambulances assigned to the borough was tracked by means of 5 colored buttons on the dispatch console. As the unit changed from Enroute to Scene, to Arrived on Scene, to Transporting to Hospital, to Available on Air, or Available at Station, a successive button was depressed by the dispatcher, tracking the ambulances status. Each unit position also had a slot to hold an assignment card.

In response to the growing call volume (now approximately 600,000 requests per year) and increasingly congested radio channels, the EMS radio system continued to expand, and in 1975 all radio transmissions moved onto the new 470 MHz UHF radio system, with each borough now having its own dedicated frequency, as well as a Citywide frequency for administrative use and Multiple Casualty Incident coordination.

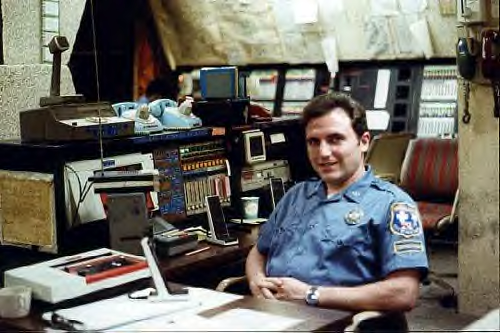

The NYC*EMS Communications Bureau moved again in October 1977 to new computer capable facilities in EMS’s new Maspeth Headquarters on 58 St.Computer Aided Dispatch recommendations replaced the manual card and belt system. MODAT’s (mobile data terminals) installed in the ambulances soon allowed the Corpsman to push a button on the console indicating a change in the units status( Enroute, Onscene, To Hospital, Available), reducing the need for voice communication.

The NYC*EMS Communications Bureau moved again in October 1977 to new computer capable facilities in EMS’s new Maspeth Headquarters on 58 St.Computer Aided Dispatch recommendations replaced the manual card and belt system. MODAT’s (mobile data terminals) installed in the ambulances soon allowed the Corpsman to push a button on the console indicating a change in the units status( Enroute, Onscene, To Hospital, Available), reducing the need for voice communication.

Photo Steve Spak

NYC* EMS has tried to utilize the latest technology to speed ambulance responses, and in 1981, the MODAT system was replaced with a vehicle mounted Mobile Display Terminal, which could display for the crew on a computer screen, the details of their assignment, hospital diversions, status of Specialty Centers (Burn, Trauma, Replant), information about other ambulances and other current assignments in their areas, as well as receive administrative messages and transmit their status updates to the dispatcher. Crews could now access the entire text of the 911 assignments to assist in prearrival planning, and aid in determining the exact location of the patient. This system was further enhanced in 1984 when the EMS computers were linked to the NYPD Sprint system, allowing faster transmission of call information back and forth between agencies, as task formerly conducted over the conventional telephone system.

With NYC*EMS now responding to 900,000 calls in 1989, radio congestion continued to be a problem. Additional voice radio capability was desperately needed, but there were no additional UHF radio frequencies available. EMS added a new trunked 800 MHz system, which allowed the Borough radio channels to be further divided, as well as adding additional administrative channels for supervisors, telemetry control, and the Motor Transport Division(vehicle repair).

While enhancing many EMS operations, this new radio system also had disadvantages. Units dispatched on an 800 frequency could not communicate with nearby units assigned to a 400 frequency. As the portable radios were not capable of receiving both bands, ambulance crews now had to carry radios for both systems. Partners could no longer remain in radio contact with each other while operating at a scene, and there were numerous radio “dead zones” in certain parts of the city due to the terrain.

FDNY brought the problems with the 800 dispatch frequencies to an end after EMS was merged into the Fire Department. FDNY had access to additional 400 MHz frequencies, and in 1997 they replaced all the 800 dispatch channels, with significant improvements in radio coverage in Manhattan and southern Staten Island.

Communications was again moved into a more modern facility within the Metrotech complex in January 2000.

In 2007 FDNY instituted a satellite based Vehicle Locator System which displays in real time, the location of every ambulance in the city. This insures that the appropriate unit closest to the call will be assigned, again reducing response time.

Telemetry Control

Medical communications for Paramedics needing to consult with a physician for medication orders had been accomplished up to this time via direct radio links to their individual base stations in hospitals around the city. The massive buildings and urban canyons of NYC often resulted in poor radio reception, or inability to reach the base station. Paramedics more often had to rely on finding a telephone near the patient. Additionally, each time a physician was needed for a radio consult, he would have to leave the patient he was treating in the hospital in order to answer the radio. This sometimes led to long delays in contact, or the paramedic being unable to initiate additional medications. Coordination of radio channels and base assignments for medical communications were handled by a paramedic assigned to a telemetry console in a large vacant room adjacent to the main communications center.

This paramedic monitored and recorded the communication between the medic in the field and the hospital physician to insure that only authorized physicians were answering the radio, and that the parties were complying with approved protocols. If a paramedic utilized a telephone for contact, there was no way to perform any quality assurance monitoring.

In 1985 construction of the Telemetry Control Center in Maspeth was completed. The center was staffed with physicians certified in Emergency Medicine and thoroughly familiar with the paramedics’ capabilities and treatment protocols. The radio system was upgraded by locating a network of voting receivers and transmitters throughout the city, resolving many of the previous problems.

In later years, the physician’s responsibilities would expand to making decisions regarding the appropriateness of Medevac requests and patient requests for transport to hospitals outside the normal transport range, A highly successful program was also introduced to deal with patients who were refusing medical care and transport, but were judged by the EMS crew on the scene to clearly be in danger if they did not seek treatment. Having the patient speak directly with our physician often convinced these patients to go to the hospital. With these conversations also being recorded, it also strengthened EMS’ position from a system liability standpoint that all possible efforts had been made to convince the patient to seek medical care.

Telemetry Control moved February 6,2003 to new facilities in Queens at the former Tuscan Building shared by the Woodside Station and Technical Services.

EARLY AMBULANCES

|

|

|

1946 — Jimmy Olson, Commissioner of the New York State Liquor Authority, and Walter Heingartner, owner of Kinney Motors Chevrolet on Coney Island Avenue Brooklyn, N.Y., incorporated J.B.E. Olson Corporation to sell aluminum-body trucks to the laundry industry. The truck, called the "Kargo King," is built for Olson by Grumman Aircraft Engineering, which produced fighter planes during World War II, with the chassis produced by Chevrolet.

1946 — Jimmy Olson, Commissioner of the New York State Liquor Authority, and Walter Heingartner, owner of Kinney Motors Chevrolet on Coney Island Avenue Brooklyn, N.Y., incorporated J.B.E. Olson Corporation to sell aluminum-body trucks to the laundry industry. The truck, called the "Kargo King," is built for Olson by Grumman Aircraft Engineering, which produced fighter planes during World War II, with the chassis produced by Chevrolet.

. 1948 — The company becomes Aerobuilt Bodies, Inc., and sells the units to J.B.E. Olson Corporation.

1948 — The company becomes Aerobuilt Bodies, Inc., and sells the units to J.B.E. Olson Corporation.

1965 — A smaller version of the Olsonette, with better vision and a Kurbside-style front, is designed. Called the Kurbside Junior, it is sold to UPS and the New York City Ambulance Service.

1965 — A smaller version of the Olsonette, with better vision and a Kurbside-style front, is designed. Called the Kurbside Junior, it is sold to UPS and the New York City Ambulance Service.

1968 — The Kurbmaster is developed and introduced to meet customer demands for easier engine access and servicing. Grumman Allied purchases J.B.E. Olson Corporation. The three plants then operate as Olson Bodies, while the sales organization operates as J.B.E. Olson.

1968 — The Kurbmaster is developed and introduced to meet customer demands for easier engine access and servicing. Grumman Allied purchases J.B.E. Olson Corporation. The three plants then operate as Olson Bodies, while the sales organization operates as J.B.E. Olson.

1974 — Grumman Allied opens a facility in Mayfield, Pa., to build UPS truck bodies.

1974 — Grumman Allied opens a facility in Mayfield, Pa., to build UPS truck bodies.

In 1974 Grumman Allied began producing Type 1 Modular ambulances and NYC EMS purtchased a slightly modified version from what they commercially sold.

Additional orders were delivered in 1979, 1984 and 1988. Each model had improvements in cabinetry, emergency lights and radio capabilities.

|

|

|

The majority of the red and white "Bread Box " Ambulances were built in 1965 by J.B.E. Olson in Garden City NY on their Kurbmaster Jr. body

EMS SPECIALTY UNITS

Dignitary Protection Unit

Owing to the nature of the times we live in, whenever the President, Vice President, or other major world leader visits New York, the U.S. Secret Service, NYPD, FDNY and other local law enforcement agencies provide an army of personnel to ensure their protection. NYC*EMS / FDNY*EMS has long been a participant in this protection plan, providing a dedicated, 24 hour Paramedic Unit to accompany the dignitary’s motorcade. The DPU is often called upon to provide coverage for multiple dignitaries simultaneously, particularly during the annual meeting of the United Nations General Assembly, when many heads of state address the body.

Only the most experienced paramedics are eligible to be considered for he DPU. These senior paramedics undergo a rigorous background investigation and receive additional training from the U.S. Secret Service in motorcade operations and interaction with foreign dignitaries and their personal medical staff. Members of the unit have received numerous commendations for their dedicated service from the White House, as well as many foreign governments.

Special Operations Division/Emergency Response Squad/ Haz Tac

The ERS was created in 1981 as the Special Operations Division under NYC*EMS. Initially consisting only of Lieutenants who had received extensive training in Incident Command and Multiple Casualty Incident management, the primary mission was to have a citywide duty officer available to respond rapidly to MCI’s. The first SOD Squad was formed in 1985 as part of the Division of Technical Services, utilizing a customized ambulance, and later a rebuilt NYPD Emergency Service Truck, with a primary mission to respond with greater capability to major MCI’s. In 1986 SOD was transferred to the Operations Division of EMS.

In 2002 there were 60 EMT’s, 6 Lieutenants, and one Captain comprising the main Squad which normally perform routine supervisory patrol and response to 911 assignments. They are assigned to custom built trucks, with a primary responsibility to respond to Multiple Casualty and Hazardous Materials Incidents. Members receive additional training in chemical, biological and radiation incident management and decontamination. All members are trained at the Hazardous Materials Technician level, capable of safely working within a contaminated Hot Zone.

In addition to the primary ERS Squads, there are also 6 BLS and 4 Paramedic HazTac ambulances on duty throughout the city which respond to normal 911 assignments until needed for a specialized response. These units also carry protective chemical suits and self contained breathing apparatus, and are responsible for initial triage and medical care at a hazardous materials incident.

Photo Jim Braunstein

ERS Squads carry limited chemical and radiological detection instruments; a resource library of toxic materials; self contained breathing apparatus and protective suits for entering areas contaminated with toxic agents; lights and generators capable of lighting a scene or an entire Emergency Department in a blackout.

At a HazMat incident, ERS works in cooperation with FDNY and NYPD HazMat teams, with FDNY responsible for detecting, containing and controlling any toxic spill, as well as physical rescue. NYPD units become involved with criminal investigation/crime scene management of any bomb or terrorist activity associated with the incident, as well as assisting with physical rescue. ERS is charged with providing initial medical care and triage of patients prior to decontamination, as well as ongoing medical care and decontamination of all victims and rescuers at the scene.

ERS was disbanded by FDNY approximately 2002, but the HazTac program continued. There are currently 35 HazTac units citywide.

Photo Will Merrins

All FDNY*EMS personnel have been trained to the Hazardous Materials Awareness level, and have received additional training in responding to chemical and biological terrorist incidents. All FDNY*EMS ambulances, paramedic units, command cars and squads carry antidote kits capable of treating a mass exposure to a chemical incident like the Tokyo sarin gas attack. FDNY*EMS also maintains strategic stockpiles of antidote kits which can be issued during a large scale incident.

Rescue Paramedics

In 2007, FDNY initiated the Rescue Paramedic program, which further enhanced the capabilities of a number of experienced paramedics. Additional training was provided in hazardous material incident management, high angle and physical rescue, and trench/building collapse. Currently there are 5 Rescue Paramedic units. Customized ambulances with additional storage space began service in 2008.

MERV’s (Mobile Emergency Response Vehicles)

Left- MERV 3 Kings County;

Right- MERV 2 Jacobi

photos-Steve Spak

MERV’s are essentially large ambulances built on a bus chassis, capable of treating or transporting multiple patients at the scene of an MCI. The first units were built in the early 70’s and stationed at Bellevue Hospital, Kings County Hospital, Jacobi Hospital, and Queens General Hospital. In the 80’s, a fifth MERV was added at Metropolitan Hospital and in the late 90's at Station 52 in Staten Island. MERV 3 pictured above, was built on a former bookmobile acquired from The Brooklyn Public Library.

Originally, when the EMS station was notified to have MERV respond to an MCI, the driver would be summoned from his regular ambulance assignment, his ambulance placed off service and he and his partner, and a designated physician from the hospital’s Emergency Department, would respond in the MERV to provide patient care along with EMS personnel from ambulances on the scene. Paramedics eventually replaced these hospital based physicians. Today the MERV’s are staffed by an designated EMT-D who is responsible for operating and stocking the vehicle, and by paramedics that meet the MERV at the scene. At major incidents, there may also be an on call physician from the Office of the Medical Director, or one of the base hospitals.

|

|

|

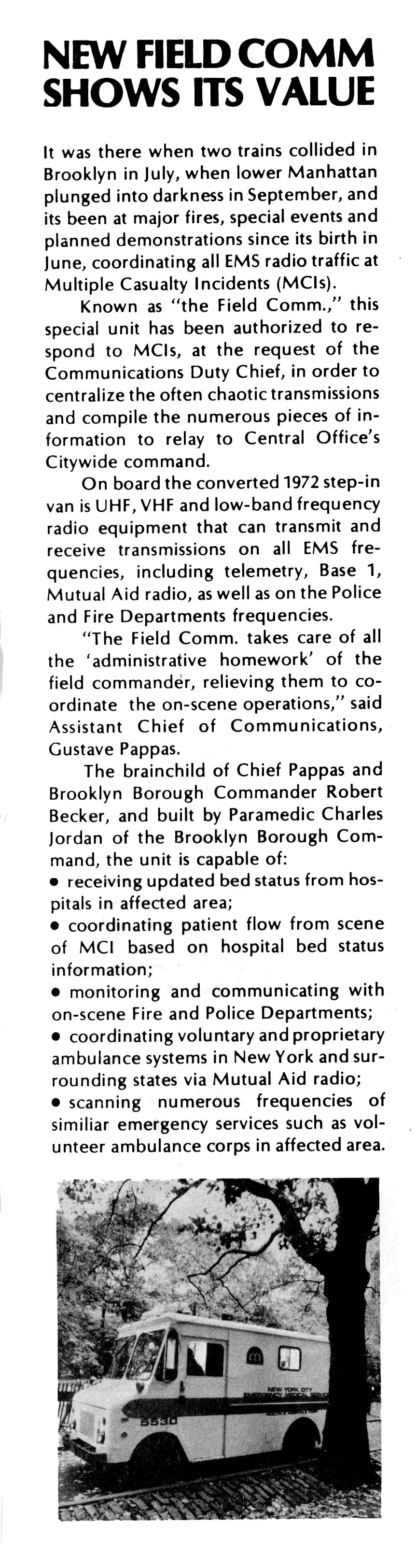

FIELDCOM

This unit serves as both an EMS command post, and a central information gathering point at the scene of an MCI. It is staffed by EMS Communications personnel and equipped with radios capable of communicating with Fire and Police units, as well as all EMS units. The Fieldcom will coordinate operations within the various EMS sectors(Triage, Staging, Treatment, Transport, Logistics, Safety) and potentially hundreds of EMS personnel at a scene, on low power local radio frequencies which will not interfere with normal continuing 911 assignments.Fieldcom will then only transmit pertinent information over the citywide MCI frequencies to the EMS Communications Center.

The first Fieldcom was built on a retired “Bread Box” ambulance in the late 70’s by Paramedic Chuck Jordan, carpenter Ralph Blank and radio shop technicians led by Don Stanton. The original ambulance was a 1965 Olson Kurbmaster Jr.

Todays vehicle is professionally built on a motor home chassis, and is equipped with its own generator, as well as cellular and hardwired phones.

Photos-Steve Spak, John Antonaides, Chuck Jordan

|

|

|

Mopeds / Cushman Scooters

EMS first experimented with having a paramedic team on Moped scooters in the early 80’s for coverage of special events such as concerts and parades. Scooters could penetrate these highly congested areas far better than an ambulance could., reaching pateients in less time. Enclosed Cushman scooters were first purchased by NYPD in the 70’s to enable police officers to expand the range of a foot post while better protecting the officer from weather and traffic. EMS purchased several of these scooters in 1986, to be utilized during the Statue of Liberty Centennial Weekend. These enclosed 3 wheel scooters were superior to the 2 wheel Mopeds because of their speed, safety and their ability to carry more equipment in an enclosed trunk.

Cushmans continue to be assigned to large parades, outdoor concerts and events such as the NYC Marathon. Each summer Cushmans details are assigned to patrol the boardwalks in Coney Island, Orchard Beach, and Rockaway, greatly reducing EMS response in these highly congested areas.

Gators

In preparation for the expected larger than usual Milleneum New Years Eve gathering in Times Square, and the possibility of citywide Y2K computer and system failures, the city purchased several Gator carts from the John Deere Co. These 6 wheel diesel powered carts were much more adaptable than the Cushman’s, in that they could transport two crew members, as well patients who are seated or on backboards, from crowded and confined scenes. The Gators also came equipped with multiple wheel drive capabilities for added traction and maneuverability off road.

In the following years, the Gators were deployed for beach patrol at Coney Island and the Rockaways. They also saw service at the site of the World Trade Center collapse, transporting both the injured and the deceased off the pile.

Experimental Star Jeep

The "Star" Jeep was an experimental vehicle manufactured by Horton in the mid 80's. Built on a 4 wheel drive Jeep Chassis, it was one of the earliest non military off road ambulance designs.

New York City EMS field tested this vehicle for use on the Coney Island, Rockaway and Orchard Beach recreational areas, but did not purchase. The Jeep proved too small, with limited ability for airway control or CPR, and were not purchased.

Motor Transport Division

Without a fleet of safe, well designed and maintained vehicles, EMS would be totally unable to fulfill its mission. MTD began under the administration of the Department of Hospitals, as “the Bronx Shop”. This single repair facility was responsible for the majority of the major repairs of all EMS vehicles. Satellite repair facilities capable of routine maintenance and minor repairs were also established within the ambulance stations of Jacobi Hospital, Kings County Hospital, Coney Island Hospital, Queens General Hospital and Seaview Hospital, staffed by a mechanic or an auto serviceman. The Bronx Shop was moved to larger and more modern facilities with the opening of NYC*EMS’ Maspeth headquarters.

During the 70’s and 80’s, the EMS ambulance fleet was plagued with mechanical and electrical problems worsened by inadequate design the and around the clock use of these vehicles: chassis that couldn’t hold up to NYC’s potholes; electrical systems that would repeatedly burn out under the load of all the emergency lights, radios, and air conditioning; vehicle fires caused by overheating transmissions; overheating cooling systems, and the lack of city funding for a regular schedule of ambulance replacements or an intensive preventive maintenance program which could replace parts before they failed with a patient onboard.

After a disastrous summer in 1988 in which a high of 54% of the fleet was out of service awaiting repair, the city finally committed to to a number of major changes. First, to deal with the immediate backlog of repairs, the repair shops of NYPD and the Department of Sanitation were temporarily enlisted to not only repair the immediate vehicle concerns, but to perform a major rehabilitation of many of the smaller items that had for so long been ignored such as torn upholstery, broken dashboard gauges, and inoperative switches.

A vehicle replacement schedule was established recognizing that the life expectancy of an ambulance on the street 24 hours a day was 5 years, not the 15 year schedule of a fire engine which sat housed in a station and only driven several hours per day. New custom ambulance specifications which spoke to the problems of inadequate cooling and electrical power were drafted which exceeded the inadequate federal specs. A vehicle design committee was established with representation of the experts in each field- MTD, Radio Repair, Technical Services, and field paramedics. The central shop at Maspeth was funded for 24 hour operation, and the satellite shops ran for 2 tours per day instead of 1.

Today we enjoy the most reliable, comfortable and well maintained fleet ever.

Medevacs

Helicopter evacuation of patients within New York City are infrequent due to limited availability of safe landing sites and a travel time of under 45 minutes to most major medical facilities. However there are circumstances, particularly involving assignments in the outer boroughs, where helicopters can significantly reduce transport time. More frequently, EMS crews will respond to designated landing zones in order to complete the transport of a patient arriving by helicopter from outside the city.

NYC*EMS/FDNY*EMS will consider use of a helicopter to transport critical patients to Burn, Replantation, or Venomous Bite Specialty centers utilizing the aircraft of the NYPD Aviation Bureau, or occasionally the US Coast Guard. Every helicopter in the NYPD fleet is equipped and NY State certified as an air ambulance, with FDNY*EMS personnel accompanying to provide medical care.

Critical Incident Stress Management Team

Day after day, year after year, EMS members respond to grisly scenes that most New Yorkers will only read about in newspapers, often encountering humanity at its worst. Memories of these events can eventually have an adverse affect on the members psychological well being. The CISM Team was established to assist EMS personnel employed by both FDNY and private hospitals in the 911 system.

The team can be requested to respond to members who have either participated in unusually stressful assignments such as large scale MCI”s, calls involving the death or serious injury to a member of the service or a child, or for those exhibiting signs of excessive stress. The team is comprised of professional psychologists and peer members who are EMS personnel who have received additional training in crisis management. Often having someone you can talk to about a difficult assignment can aid the member in coping with the situation.

|

|

|